-

Flyer for the Twentieth Century German Art exhibition (1938), featuring Franz Marc’s Blue Horses.

© Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.Introduction

2018 marks the eightieth anniversary of the Twentieth Century German Art exhibition, held in the New Burlington Galleries in central London between June and August 1938. This was the largest international response to the National Socialist campaign against ‘degenerate’ art, and it remains the largest display of twentieth-century German art ever mounted in Britain. This exhibition, originally staged at The Wiener Holocaust Library from 13 June 2018 to 14 September 2018 and produced in partnership with the Liebermann-Villa am Wannsee in Berlin, draws upon The Wiener Holocaust Library’s archival collections to explore the history and contexts of the Twentieth Century German Art show, and features original works from the 1938 exhibition.

-

Nazi Cultural Policy

Image of a sculpture, HJ (Hitler Youth) Drummer by Anni Spetzler-Proschwitz (1938), featured in the Great German Art Exhibition in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich in 1939.

© Kaminski, Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.Culture was of central importance to the Nazis’ racist worldview. They believed that the Germanic ‘Aryan’ race was culturally supreme. Nazi-sympathising organisations, such as the Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (Militant League for German Culture, established in 1928), promoted the idea of ‘pure’ German culture.

Emil Nolde: Junger Gelehrter | The Young Academic, 1918. Oil on canvas. © Kunstmuseum Gelsenkirchen Nazi artistic ideals reflected a cult of masculine ‘Aryan’ vitality that was connected with notions of military strength and racial purity. Classical tropes and Nordic myths were a source of inspiration for visual artists working within the parameters that the Nazis set out. Nazi-approved culture also emphasized ideals of traditional motherhood and a mystical German connection to the soil.

The Nazis believed that they were defending German culture from corruption by foreign or ‘degenerate’ influences. They condemned the artistic endeavours of German Jews and those influenced by modernist or communist ideas. Products of American culture were also vilified, particularly jazz music. Until the mid-1930s, the Nazis tolerated the work of some non-Jewish German modern artists, like Emil Nolde, a member of the Nazi Party. Eventually, however, most manifestations of modernism were labelled as ‘degenerate’ and un-German, including the work of Nolde.

-

The Campaign Against Modern Art

Advertisement for the Entartete Kunst exhibition, Munich 1937. It reads: ‘NSDAP [National Socialist] exhibition in the Haus der Kunst at Königsplatz. Tickets here. At reduced advanced sale prices.’

© Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.From 1937, the regime launched an energetic campaign against the art that they considered unacceptable. Around 16,000 works by modernist artists, including Pablo Picasso, Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde were seized and removed from German galleries and museums. Artists were sacked and banned from working. Many artists, supporters and collectors of German modernism were forced into exile.

The Entartete Kunst exhibition, a large Nazi-organised show featuring hundreds of works of seized from German museums, was held in Munich’s Archaeological Institute in 1937. The exhibition aimed to denigrate modern art and promote the idea that the Nazi Party were the defenders of German culture.

At the same time, a second show was staged in Munich, the first annual Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German Art Exhibition). This exhibition was designed as a showcase of the art which was approved of by the National Socialist government.

“We will from now on, lead an unrelenting war of purification…, against the last elements which have displaced our Art.”

Adolf Hitler speaking at the Day of German Art, Munich, 18 July 1937. As a young man, Hitler wanted to be an artist. He believed modern art was corrupt and that all art should be figurative.

-

-

The Reich Chamber of Culture Law

The Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda is commissioned and empowered to combine the members of the professional groups in his area of responsibility in corporations under public law.

In accordance with the above the following entities will be established:

– Reich Chamber of Literature

– Reich Chamber of Press

– Reich Chamber of Broadcasting

– Reich Chamber of Theatre

– Reich Chamber of Music

– Reich Chamber of Visual ArtExtract from the Reich Chamber of Culture Law of September 1933.

The Law was signed by Hitler and by Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Josef Goebbels.

Once in power from 1933, the Nazis set about trying to control and coordinate the production of culture in Germany under the direction of the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda.

-

Flight From Persecution

Political and racial persecution drove people to flee Nazi Germany and later Nazi-occupied areas, such as Austria and Czechoslovakia. Some of those who left had been targeted in the campaign against modern art.

Britain was one destination for refugees in the 1930s, but there were many obstacles to gaining entry. Migrants to Britain had to have an offer of employment or prove to immigration officials that they had sufficient means to support themselves. Most refugees were only given temporary residence.

Following an upsurge in the numbers of Jews seeking asylum in Britain after the German takeover of Austria (the Anschluss) in March 1938, bureaucratic barriers increased. Visas were introduced for those arriving from Germany and Austria. Nevertheless, by the time the Second World War started in September 1939, around 80,000 people escaping Nazi persecution had arrived in Britain.

-

Refugees and Culture in Britain

De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill, Sussex (on the right), designed by Jewish-German architect, Erich Mendelsohn, postcard from the 1930s.

Courtesy of Bexhill Museum.Entry into Britain was not always easy, but once here, many refugees and exiles managed to establish connections in Britain that enhanced and invigorated the cultural scene. Erich Mendelsohn, who had fled from Berlin in 1933, won the competition in 1935 to build the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill, a building regarded as an outstanding example of modernism in Britain. Refugees from Germany also helped develop the Glyndebourne Festival from 1934 and later the Edinburgh International Festival.

Berlin-based photographer Gerty Simon travelled to Britain in 1933 and re-established her studio in Chelsea. She photographed many of the leading figures of the day, including Aneurin Bevan, Peggy Ashcroft and Sir Kenneth Clark, then-director of the National Gallery and patron of the Twentieth Century German Art exhibition.

Alfred Flechtheim (seen in the photo below) was a Jewish-German art dealer who specialised in avant-garde art. The Nazis drove him out of business early on in their rule and seized his gallery. Flechtheim fled to Paris in 1933, then to London. He died in 1937.

-

-

The London Exhibition – Twentieth Century German Art

Brochure cover for the Twentieth Century German Art exhibition.

© Wiener Holocaust Library CollectionsExactly one year after the twin propaganda exhibitions in Munich, the exhibition Twentieth Century German Art opened its doors in London. The 1938 London show contained over 300 examples of German modernist art, paintings, sculptures and works on paper by over 60 artists, among them Max Beckmann, Max Liebermann, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, George Grosz, Otto Dix and Kurt Schwitters.

Twentieth Century German Art was not only the first major retrospective of German modernism in the English-speaking world, it was also the largest international response to the Nazi campaign against so-called ‘degenerate’ art. All but one of the exhibited artists had been derided as ‘degenerate’ in Germany, seen their works confiscated from German museums, or been forced into exile from the Third Reich.

Recent research has revealed the complexity of staging the exhibition, and the challenges organisers faced in bringing together such an extensive and varied exhibition. Ultimately, a remarkable diversity of lenders were prepared to contribute works. Alongside British and Swiss private collectors, dealers in London and Paris and museums in Basel and Luzern they included scores of German emigrés – artists and collectors – sending works from countries across Europe as they sought to escape the Third Reich.

-

Organising the Exhibition

Flyer for the Twentieth Century German Art exhibition (1938), featuring Franz Marc’s Blue Horses.

© Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.The exhibition was organised by three initially separate groups of people: the gallerist Noel Norton in London, the dealer Irmgard Burchard and her husband, the artist Richard Paul Lohse in Zürich, and a circle based around the émigré art critic Paul Westheim in Paris. Over the winter of 1937-38 they became aware of each other’s plans to stage a response to the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition, and began working together on an exhibition in London.

In a little over eight months, the organisers gathered works from over 90 individual collections for the exhibition in London.

The exhibition was originally planned under the more openly political title Banned Art. The title deterred some potential lenders, particularly those based in Switzerland, and so by February 1938 it had been changed to Twentieth Century German Art.

-

Gathering the Artworks

German modernism was not widely collected in Britain during the 1930s. The organisers therefore turned to European collections to stock the London exhibition. A number of pieces came from museums and private collections in Switzerland. Hundreds of works came from Germans in exile, including Chemnitz industrialist Karl Göritz in Holland, Hanau lawyer Ernst Nelkenstock in London, and left-wing politician Wilhelm Abegg in Zürich.

Another important source of loans was the so-called ‘degenerate’ artists themselves, including Max Beckmann, then living in Holland; Wassily Kandinsky in exile near Paris; Paul Klee, who had returned to his home country of Switzerland after 1933, and the sculptor Benno Elkan, who was by 1938 based in London.

-

Article reporting on the opening of Twentieth Century German Art, in The Star (London), 7 July 1938, p. 1 (detail).

Private collection.Reception of Twentieth Century German Art in Britain

Before 1938, there had been very few exhibitions of modern German art in Britain. Nevertheless, the exhibition Twentieth Century German Art proved extremely popular with the London gallery-going public. The exhibition’s opening on 7 July 1938 attracted over a thousand people: the propaganda exhibitions in Munich during 1937 had been widely reported in Britain, and the political significance of the London show was clear, despite the show’s neutral title.

By mid-August, an estimated 12,000 visitors had seen the show. This popularity caused the exhibition to be extended three times past its original end date, eventually closing on 27 August 1938.

British critics were open-minded about the quality of the art on show. While some journalists found the German modernists inferior to those of France, many found the German show a refreshing change, imploring their readers to visit the exhibition.

-

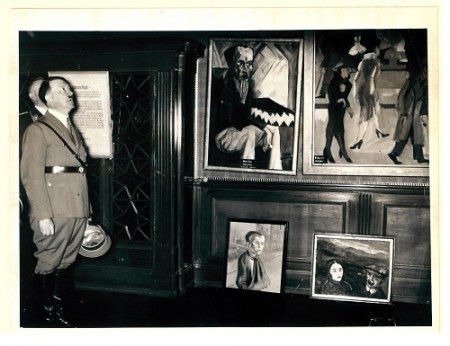

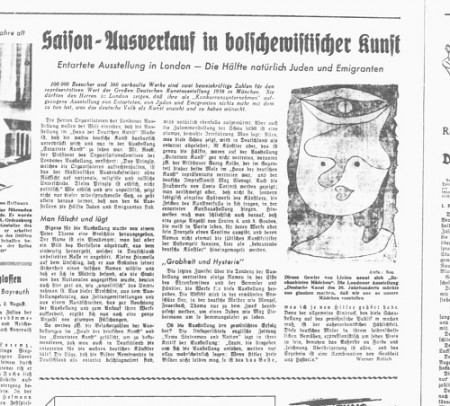

German Art which appeared in the Berlin-based newspaper Der Angriff on 3 August 1938, p. 4.

Private collection.Reception in Germany

In Nazi Germany, Twentieth Century German Art prompted a furious reaction. Adolf Hitler himself spoke out against the show at the opening of the second annual Great German Art Exhibition in Munich on Sunday 10 July 1938. Various angry reports followed in the Nazi-controlled German press. For example, in the Völkischer Beobachter, which characterized the show as ‘Judaism and Moscow’ presenting lies to the ‘politically clueless English’.

London 1938: Defending ‘Degenerate’ German Art

Exhibition Type: Online Exhibition