-

Deported Jews on the Czechoslovak-Hungarian border, 1938

© B. Birnbach (WL15019)Overview

Ongoing violence and upheaval in Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq and Sudan today has created an upsurge in the number of refugees fleeing conflict, in what is commonly referred to as a refugee ‘crisis’. Conflict and war, political, religious and ethnic persecution have always caused the mass displacement of populations. In Europe in the 1930s and 1940s, economic and political breakdown and the rise of extremist politics turned citizens into refugees. From 1933 and 1934, people began to leave Germany and Austria to escape political and other persecution, and after 1936, thousands more fled the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s regime. Refugees also left Italy at this time.

In the late 1930s, Nazi persecution of Jews in Germany and the takeover of Austria (1938), Czechoslovakia (1938-39) and Poland (1939) produced Jewish refugees – before the Holocaust itself commenced. By 1946, war, genocide and forced population movements had created over fifty million refugees and displaced people in Europe.

Whilst many well-known refugees reached Britain during this period, including Sigmund Freud, here we focus on the stories of ‘ordinary’ people. Jews were particularly affected by the refugee crisis of the 1930s and 1940s: two thirds of Europe’s Jewish population were murdered in the Holocaust.

The Wiener Library was founded by Alfred Wiener, himself a German Jewish refugee, and its archives have been enriched by the collections of Jewish refugees in Britain. It is their voices and experiences that form a significant part of this exhibition.

-

Map showing the distribution of Russian and Armenian refugees after World War I. Published in The Red Cross and the Refugees by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Wiener Library Archive. -

‘The Situation of the Refugees in Spain’, 1937. Pamphlet published by the International Bureau for the Right of Asylum and Aid to Political Refugees. Wiener Library Archive. -

‘Child Victims of New Germany’, c. 1935. Pamphlet written by Violet Bonham-Carter. Wiener Library Archive.

-

-

Hans Kohl’s Austrian Centre membership card. The Austria Centre provided assistance and cultural activities for several thousand refugees from Austria.

Wiener Library ArchiveEve Kolmer

‘With a suitcase and a pound in my pocket’

Eva Kolmer (1913-1991) was one of the approximately 30,000 Austrian Jews who came as refugees to Britain before the Second World War. From 1934-1938, most of those who left Austria were escaping political persecution.

Kolmer was a member of the Austrian Communist Party in Vienna, and she spent four months in prison after a semi-fascist regime gained power in 1934. Following the German annexation of Austria (Anschluss), Kolmer was advised to leave. She departed with only ‘a suitcase, a ticket to Zürich and a pound in [her] pocket’, and ended up in Britain, where her visa was sponsored by the editor of The Spectator magazine.

Kolmer was instrumental in establishing The Austrian Centre for Austrian refugees in London. After the November Pogrom (Kristallnacht) on 9-10 November 1938, the number of Jewish refugees from Austria increased, and the Austrian Centre provided crucial support. After the war, Kolmer emigrated with her husband to East Germany, where she pursued a career in paediatric medicine.

-

The British Government and Refugees in the 1930s and 1940s

The British Government could act entirely at its own discretion in deciding which refugees to accept in the 1930s. There was no legal concept of right to asylum, and refugees mainly attempted to enter Britain via established immigration procedures.

Before the German annexation of Austria (Anschluss) in 1938, border control officials determined whether political refugees or those escaping ethnic persecution could enter Britain. Refugees had to meet various criteria or be privately sponsored or self-supporting. Eligibility was not based upon the refugee’s experience of persecution, and the British Government provided no funding for refugees. It was easier to obtain entry to Britain if one were wealthy or had what was deemed a ‘useful’ profession. Some were only allowed in on the understanding that they would settle elsewhere permanently. Others came on the Kindertransport scheme or as domestic servants.

After the Anschluss, the number of people seeking refuge in Britain increased, and in April 1938 the British Government introduced a visa system to regulate the process. Those in certain professions were often given priority. By the start of the war in 1939, Britain had given refuge to approximately 80,000 people, mostly Jews escaping Nazi oppression.

From this time the British Government began to fund the sponsorship of refugees, but largely shut down official channels for migration from German-occupied Europe. Many refugees in Britain found their relatives were stranded. Britain blocked moves to allow more Jewish immigration to Palestine during and after the war, and also would not assure neutral countries that it would take Jewish refugees.

After the war, almost all refugees were allowed to remain permanently in Britain, and most chose to do so. The government generally recognised, in the aftermath of the Holocaust that, in the words of Sydney Silverman MP, it was cruel ‘to compel [Jews] against their will, to go back to the scene of these crimes’.

However, the British Government did not want to accept many more Jewish refugees. Some were permitted entry as ‘domestics’ or under the Home Office’s Distressed Relatives Scheme. 732 Jewish child survivors, mainly boys, were also accepted, and 86,000 Displaced Persons, including many Poles, were resettled in Britain between 1947 and 1949. A minority of the admitted Displaced Persons (DP) were Jews, and some post-war DPs had been collaborators or war criminals.

-

Ruth Peschel, identity document, 1939. Peschel came to Britain on the Kindertransport. Wiener Library Archive. -

Letter from the Chief Inspector of the Aliens Tribunal, Brighton Area, to Johanna Behrend, 9 October 1939, summoning Behrend to a tribunal to determine whether she should be interned as an Austrian or German ‘Alien’. Wiener Library Archive. -

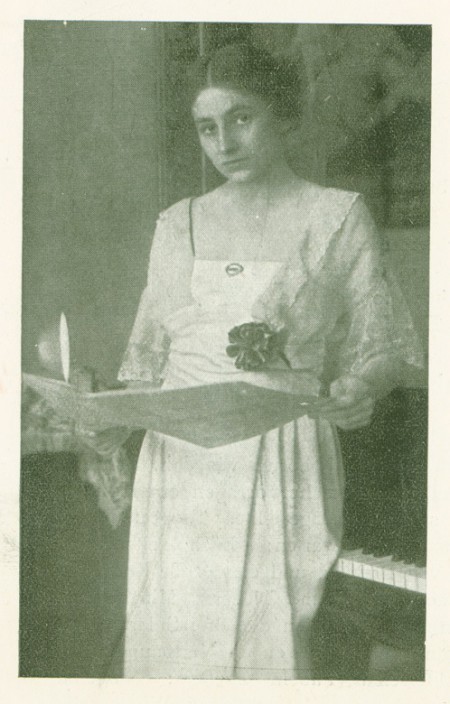

Publicity image of Behrend in her days as a singer in Germany, c.1918. Copyright unknown – image taken from a ‘singing programme’. Wiener Library Archive.

-

-

Photograph of internees in Douglas, Isle of Man, 1940 Surveillance and Detention

Wiener Library Archive; WL8139

At the start of the war, all migrants from Germany and Austria resident in Britain were subject to certain restrictions, but only Nazi sympathisers were actually interned. In the spring and summer of 1940, at a time of dramatic Nazi military successes, anti-foreign feeling and fears of enemy infiltration peaked.

Following pressure from the right-wing press, around 27,000 Jewish refugees were now also interned as ‘enemy aliens’. Most were released by autumn 1940. Some Jewish refugees coped relatively well with internment, whilst others, such as composer Hans Gál, found it a traumatic experience.

-

Photo of Bernard (Bernd) Simon as a boy, with pages from his diary written aboard HMT Dunera, 1940.

Wiener Library Archive; WL15354.Bernd Simon

Bernard (Bernd) Simon was born in Berlin in 1921. His father, Wilhelm, was a lawyer, his mother Gerty a well-known portrait photographer. He attended Anna Essinger’s progressive school in Herrlingen. The school was not exclusively Jewish, but with a large number of Jewish staff and students and a liberal ethos, Essinger felt that her work could not safely continue in Germany after the Hitler became Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933. Essinger took steps to re-locate abroad, and later the same year, under the guise of a school trip to London, staff and students came to Britain and the school was re-established in Bunce Court, Kent. Gerty Simon accompanied her son to Britain and re-established her photographic studio in Chelsea. Amongst her sitters in London was Dame Peggy Ashcroft.

In 1940, male teachers at Bunce Court, and male students over 16 were interned by the British authorities as ‘enemy aliens’, despite having come to Britain essentially as refugees from Nazi Germany. Bernard’s father, who had managed to get sponsorship to come to Britain as a refugee in the late 1930s around the time of Kristallnacht, was also interned, although he was released quickly. Bernard, along with 2,500 other young men was sent aboard the ship Dunera to be interned in Australia. Four fifths of those aboard were Jewish. Conditions abroad were notoriously bad, and Bernard later claimed compensation for the theft of his belongings aboard. In Australia, he was interned in Hay Camp. Bernard kept diaries of his time in internment and aboard the Dunera.

Bernard Simon died in September 2015. His partner Joseph Brand donated the collection to us in 2016. In later life Bernard held a top position in the Time Life organisation. He was naturalised in 1947.

-

Refugees, International Organisations and the Second World War

Staff of the British Red Cross Society Staff in Occupied Germany. Photograph by Owen & Moroney, London.

Wiener Library Archive; WL4558.In July 1938, an inter-governmental summit to discuss the plight of Jewish refugees from Germany, held in Évian, France, failed to reach an agreement. The Second World War left a vast number of refugees in its wake, and in 1943, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency (UNRRA) was founded to respond. The organisation, which included 44 member countries, attempted to help Displaced Persons (DPs) in Europe with humanitarian aid and determined eligibility for assistance. Working alongside military authorities, UNRRA helped thousands of DPs with resettlement and repatriation, and by the start of 1946, three quarters of DPs had returned home. Around twelve million ethnic Germans who lived in Central and Eastern Europe and who were expelled after the war had become refugees, but were not eligible for assistance.

In DP camps and urban centres in the Allied zones of occupation, UNRRA provided relief to survivors of Nazi persecution and other displaced people, although policies in the British zone did not define Jews as a distinct category for assistance. Within the context of the brewing Cold War, by 1947 UNRRA’s priorities shifted. Being anti-Communist became a crucial determinant of whether people were deemed eligible for UNRRA’s help. Some wartime perpetrators from the Baltic states and Yugoslavia were assisted by UNRRA with resettlement at this time if they could prove they were sufficiently anti-communist. In July 1947, the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) took over UNRRA’s work.

The Red Cross (founded 1863) provided refugees during and after the war with food, shelter and medicine, and helped families separated by persecution and war to remain in contact. The Red Cross, UNRRA and its successor, the IRO, helped trace and reunite surviving relatives, efforts that coalesced into the establishment of the International Tracing Service. The 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention defined the term ‘refugee’ and legally codified practises of granting asylum that had been in existence for some time.

-

Jewish Responses in Britain

At the Jewish Refugee Committee’s offices in Woburn House, where Bloomsbury House was moved, late 1930s. Copyright unknown.

Wiener Library ArchiveBefore the Second World War, Anglo-Jewish Communities intervened in response to the plight of Jews in Germany, even whilst facing domestic concerns, including increasing antisemitism.

The Central British Fund for German Jewry (CBF) raised millions of pounds for the Jewish Refugee Committee (JRC, also known as the German Jewish Aid Committee) and other groups to support refugees. Founded in October 1933, the JRC assisted Jewish refugees with housing, medical care, and training. The Refugee Children’s Movement (RCM) helped organise the emigration and resettlement of Jewish children selected for the Kindertransport after the Government agreed to waive visa requirements for those sponsored by the Children’s Inter-Aid Committee. The RCM worked alongside B’nai B’rith and the Women’s International Zionist Federation and other groups, such as the Quakers. The Chief Rabbi’s Religious Emergency Council, led by Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld, organised transports of children, rabbis, shochets (ritual slaughterers) and teachers to Britain, and settled them in Orthodox communities. The Lord Baldwin Fund, Council for German Jewry and British ORT also supported refugees. The Academic Assistance Council (later, Council for At-Risk Academics, CARA), founded in 1933 by William Beveridge, assisted academics that were forced to flee Nazi Germany.

Not all Jewish refugees who came to Britain benefited from the assistance of an aid organisation. This resulted in the creation of networks of support by refugees, for refugees. Founded in 1941, the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR) strove ‘to represent all the Jewish refugees from Germany for whom Judaism was a determining factor in their outlook on life’. The AJR provided legal and social services, and it worked to build political will for the acceptance of Jewish refugees in Britain after the war. The AJR organised meetings and published information for members in the AJR Information (later AJR Journal).

Jewish refugees organised mutual aid associations and social clubs around professions, culture, religious communities and other interests, some of which were coordinated by the AJR. For instance, the AJR supported The Hyphen, which was a group established in 1948 by Peter Johnson (Wolfgang Josephs) for younger Jewish refugees.

-

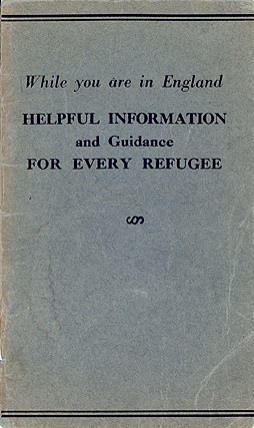

‘While You are in England: Helpful Information and Guidance for Every Refugee’. Pamphlet published by the German Jewish Aid Committee and the Board of Deputies. Wiener Library Archive. -

Table Showing Main Committees in Bloomsbury House, c. 1943. Wiener Library Archive. -

AJR Information, Issue No. 5, May 1946. Journal published by the Association of Jewish Refugees. Wiener Library Archive.

-

-

Published in the Daily Herald, December 1938.

Wiener Library Archive; WL30.Somewhere Else: Life as a Jewish Refugee in Britain

After being forced to leave, Jewish refugees who managed to reach Britain had to adjust to a new country whose language and culture was not their own.

Many refugees benefited from the help of organisations as well as generous individuals. However, the obstacles they faced – adapting to new, not always sympathetic surroundings and coping with the loss of family, profession, and homeland – were tremendous.

Moreover, Britain was at war, and refugees endured shortages and bombings like other residents. Jewish refugees lacked extensive personal networks, and unlike Polish or Czech refugees, they did not have national representation by a government-in-exile. Nearer to the end of the war, they were uncertain about whether they could or should stay in Britain. The overwhelming majority of Jewish refugees who came before the war became naturalised citizens after war’s end and attempted to pick up the pieces of their lives. While many settled in London, other cities such as Manchester also received refugees.

-

Loss and Hope

The circumstances of emigration shaped Jewish refugee communities in Britain. Because of entry requirements, many Jewish refugees in Britain were professionals, scholars or well-known artists with resources to emigrate and networks to obtain visas and sponsors. Couples without children and younger people were able to emigrate more easily than the elderly and poor.

Child refugees, separated from their parents and sent on the Kindertransport, faced particular challenges. They were dependent on the generosity of strangers and more susceptible to abuse or exploitation. Older children and adolescents placed in youth hostels found some camaraderie, but were still separated abruptly from the familiar. Both men and women coped with poverty and the loss of their professional lives, taking on menial labour to scrape by. Thousands of women who came as domestic servants, often with little or no training, were underpaid, sometimes maltreated, and subject to hostility and class discrimination. In many refugee families, women stepped into the breach and became the main breadwinner, adapting to jobs as cooks and cleaners, as men sometimes were not allowed to practice their previous professions in Britain.

‘I’ve been working as a waitress in Lyons for the last two weeks, earning anything between two to four pounds a week, which means I’m getting by quite well. Apart from work I hardly see anyone nowadays. I stay home and don’t want to go out anymore…I’m beginning to feel very disappointed with life. The last few years haven’t brought me any happy memories. Nothing much nice has happened in my youth.’

Ilse Shatkin (née Gruenwald), A young Jewish refugee, 21 January 1942 diary entry

-

Two child survivors of the Holocaust, Eva (left) and Hanka Taub, at the Weir Courtney Hostel, Lingfield, 1946-7. Weir Courtney was one of several hostels that received child survivors after the war. Copyright unknown. Wiener Library Archive; WL6170. -

Purim Party at the Beacon Rustal Refugee Home near Tunbridge Wells, 1940. Copyright unknown. Wiener Library Archive; WL8137. -

First page of ‘Unsere Zeitung’, Schlesinger Hostel Children’s Newspaper, 1939. Wiener Library Archive

-

-

Serving to Survive: Domestic Servant Refugees in Focus

Before the war, a third of all Jewish refugees – more than 20,000 women – came to Britain on visas granted for domestic service. British Government policy in this regard was both opportunistic and humanitarian: it aimed to fill a gap in the labour force whilst also recognising that the women, who were often middle class and had no formal training, would likely not remain in these positions.

Jewish women determined eligible for domestic service visas were placed in both Jewish and non-Jewish homes across Britain, a process administered by Bloomsbury House. In some homes, they were treated well, but in many cases they were exploited and their wages were meagre. Their employers often showed little sympathy for their circumstances as refugees. After the German invasion of Poland, suspicion about ‘enemy aliens’ at home prompted widespread dismissals of refugee domestics and some were interned. During the war, many happily found work elsewhere and contributed to the British war effort.

Despite these hardships, refugee domestic servants were resilient. They became the main breadwinners of their families, separated from spouses and children, whose fates sometimes remained unknown to them. They created networks of support and campaigned for better work conditions, with little to no trade union help.

‘I cannot think with affection of the time I spent as a domestic.’

Marion Smith

-

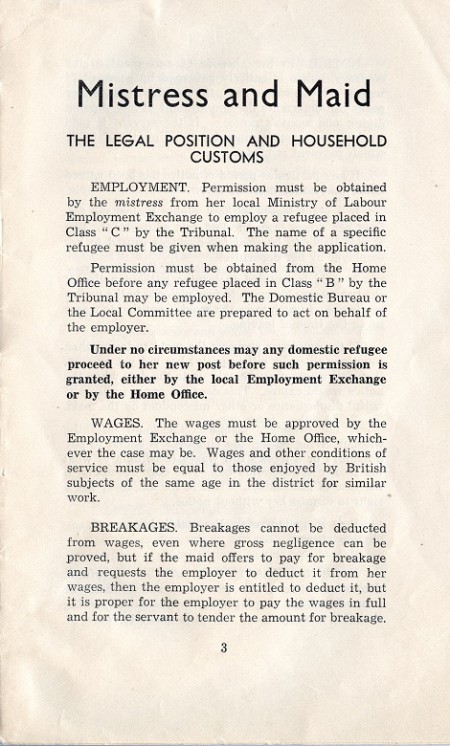

Page from Mistress and Maid pamphlet, produced by Bloomsbury House. Wiener Library Archive. -

Letter from Mrs S Hurst to Miss Frieda Mandel (then Newton), dated 24 February 1939. She came to England in 1939 as a domestic servant and recalled that she was poorly treated. Wiener Library Archive. -

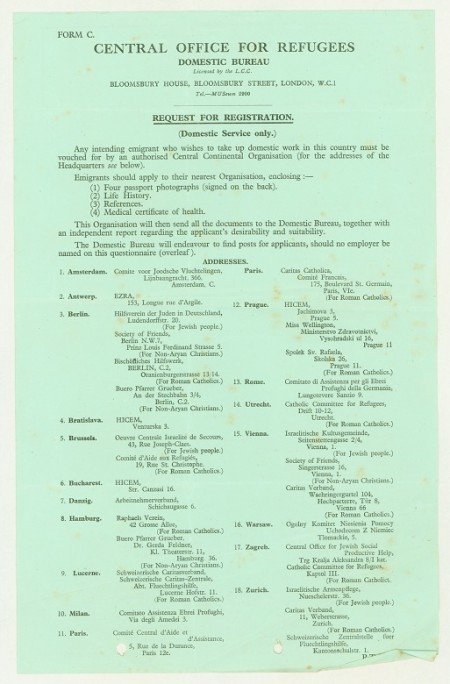

Form C., Central Office for Refugees, Domestic Bureau, regarding the application process for domestic service. Wiener Library Archive.

-

-

Crowd outside the Swiss legation in Budapest, Carl Lutz, 1944.

Wiener Library Archive; WL7215The Media and Forced Migration

‘But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought. A bad usage can spread by tradition and imitation even among people who should and do know better…’

George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language”, 1946

Both the displacement of people as a consequence of war and atrocity and representations of refugees as ‘floods’ are increasingly commonplace. The headlines are familiar. So too is the range of humanitarian interventions and governmental responses routinely triggered by mass movements of people.

Patterns in media discourse and representation from the past and present often categorise refugees and migration, distinguishing between those who are ‘deserving’ and ‘eligible’, and those who are not. A symbiosis between media and policy contributes to the perception of migration and immigration as crisis: a perpetual, intractable problem. Policy is transmitted to media, whose stories, often shared rapidly via social media, then feed back into policy. This cycle encourages a ‘language’ of migration. It is this language, with its use of dehumanising and anaesthetised terms, that often has the power to corrupt thought and action.

Consider media representations related to crises of mass displacement. Why do some waves of migration elicit sympathy, while others hostility? How do these examples offer insight into the shortcomings of humanitarian, national and popular responses? What are the lessons – if any – from history?

-

© Pearl Law Visitor Voice, Thought and Responses to the Exhibition

A key aim of the exhibition was to provide the space to give visitors an opportunity to reflect. Visitor voice, thought and responses towards the exhibition, A Bitter Road: Britain and the Refugee Crisis of the 1930s and 1940s were essential in the creation of this exhibition.

The exhibition drew parallels between Britain’s past and Britain’s response today to our current political, economic and social crisis, in particular [sp] reference to the current refugee crisis. One of our current volunteer bloggers, Yehia Nasr published an acocunt on this topic entitled, Exploring Europe’s Responses to the 2015 and post-WWII Refugee Crises.

One visitor, Pearl Law, produced an amazing set of sketches which brought each personal story to life and helped to highlight their relevance and resonance today. See this series here.

Whilst viewing the exhibition visitors were asked to consider what else can be done for refugees and what they personally could pledge to do in order to help ease the current refugee crisis.

-

Exhibition Catalogue

An exhibition catalogue featuring photographs and documents from our collections, case studies featured in the exhibition, and further information on the refugee crisis of the 1930s and 1940s is available to purchase via the Library’s online shop.

A Bitter Road: Britain and the Refugee Crisis of the 1930s and 1940s

Exhibition Type: Online Exhibition